Public and social housing providers are navigating the need to retrofit buildings for energy efficiency and reduced carbon footprint. Cost and the logistics of relocating tenants during renovations can pose significant challenges. It is therefore essential to understand a building’s life cycle so that we can build and retrofit with the future in mind. How can we avoid relocating residents during renovation? Are we adapting to respond to region-specific natural hazards that will likely intensify? And, most crucially, are we responding to the real needs of the tenants we serve?

“Sustainability is a global goal, but the way to achieve it must be site-specific. True sustainability in the construction industry is ecoefficiency, safety, and resilience all pursued at the same time, explained Professor Alessandra Marini from the University of Bergamo during our latest Sustainable Construction Topic Group meeting. “We need to inform, consult, engage, and empower people living in the buildings.”

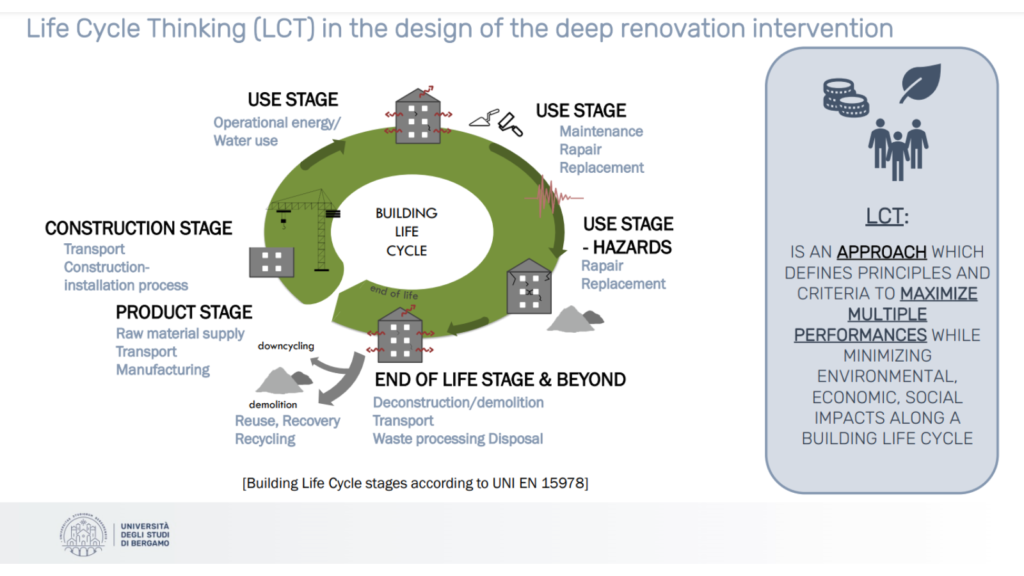

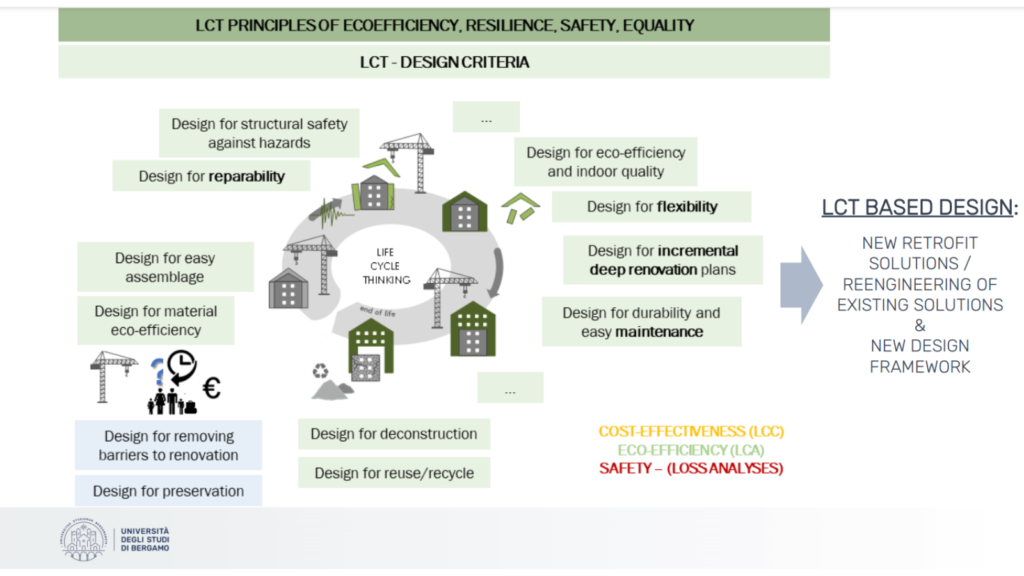

Professor Marini explained how the Life Cycle Thinking strategy can help to guide design and transition towards a low-carbon society. While Life Cycle Analysis is an important tool to measure impacts, the Life Cycle Thinking framework serves as an approach to retrofit buildings to maximise performance. Deep renovation interventions can therefore also aim for easy assembly, reparability, and structural safety against hazards. Additionally, buildings can be designed for deconstruction, reuse, and recycling as needs change.

The Life Cycle Thinking Process

“The Life Cycle Thinking process can lead to the re-engineering of traditional methods,” stated Professor Marini. For instance, opting for a reparable structure, equipped with structural fuses to mitigate damage from natural hazards, allows for repair work without relocating residents. Moving from shear walls to standardised modular components can also facilitate disassembly and reuse, increasing design flexibility.

The Life Cycle Thinking approach was used to re-develop a social housing building managed by Aler BCM (Italy). Read more about this in our Best Practice Library.

This approach was also successfully applied in the renovation of a gym hall in Brescia, Italy, responding to the high earthquake risk in the area. The structural design incorporated a hybrid wood-steel exoskeleton and replaceable seismic fuses, transforming the building from seismic category F to A. Energy efficiency features, including a thermal insulation layer, improved efficiency from E to B. In addition, the renovation triggered further renovation of the area.

Data-driven renovation

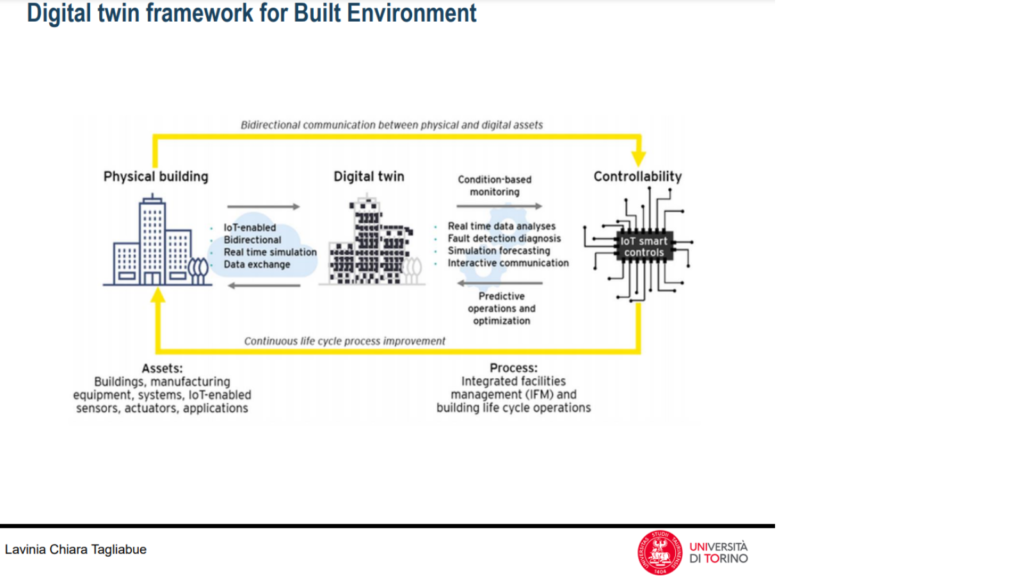

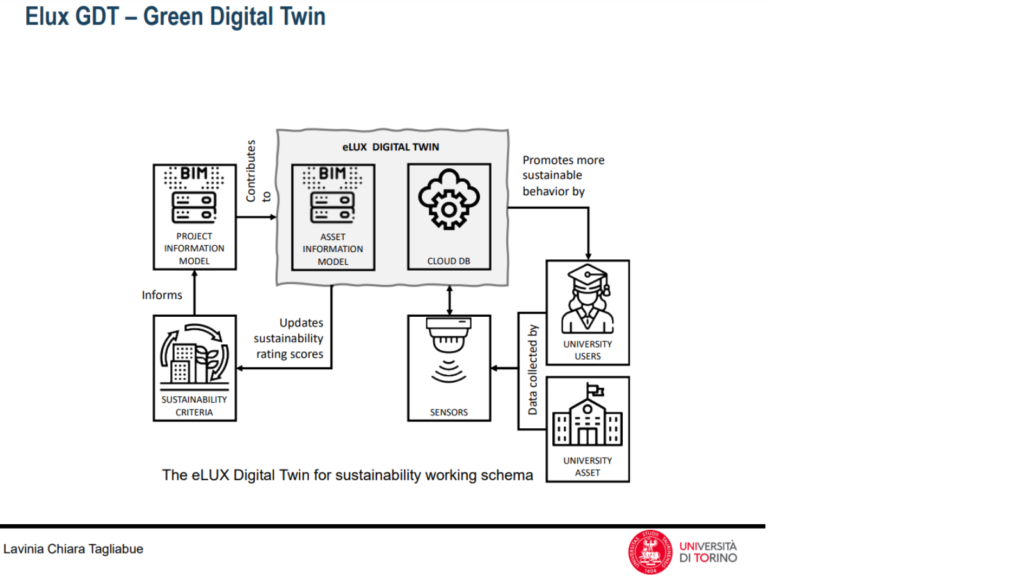

A digital twin played an important role in the gym hall renovation project. Enriched with real-time data, digital twins can serve as a digital framework for sustainability. “The digital twin is a replica, and the data connects the real space and the virtual space. It allows us to shift from static calculations to dynamic monitoring of criteria for sustainability,” explained Professor Lavinia Chiara Tagliabue from the University of Turin.

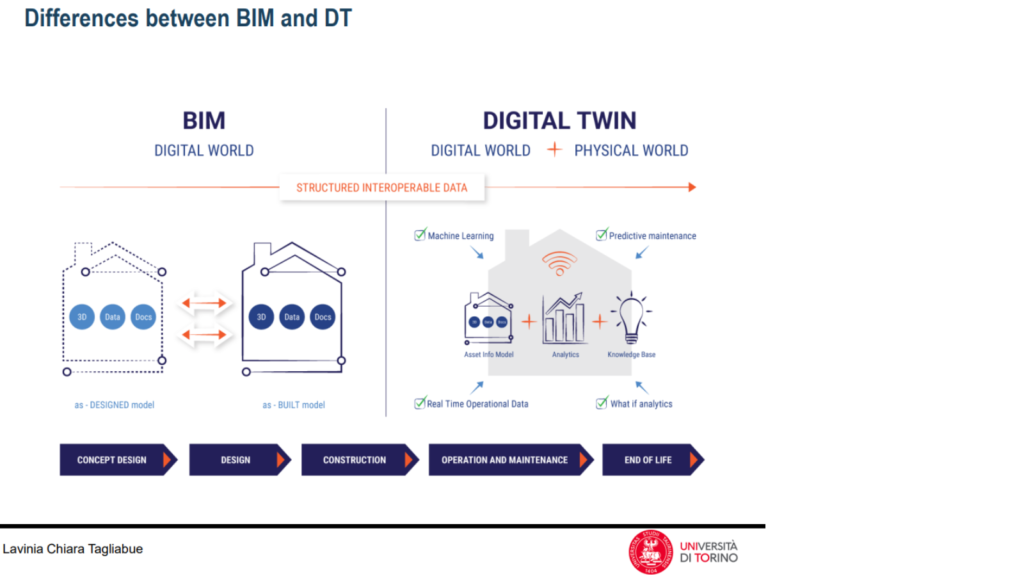

Such tools must be used correctly to have an impact on our work. Professor Tagliabue emphasised the different practical uses of the digital twin compared to Building Information Modeling (BIM) throughout a building’s life cycle.

While BIM aids in design, construction and deconstruction phases, the digital twin focuses on the dynamic monitoring and optimisation of site operations and building usage. Data flowing from the physical building can help us to understand how to increase the quality of use of the building. For instance, we may gather data from sensors on energy use or to know when to repair materials. We may also simulate and track the flow of people, ventilation, and light.

Digital twin to improve indoor conditions

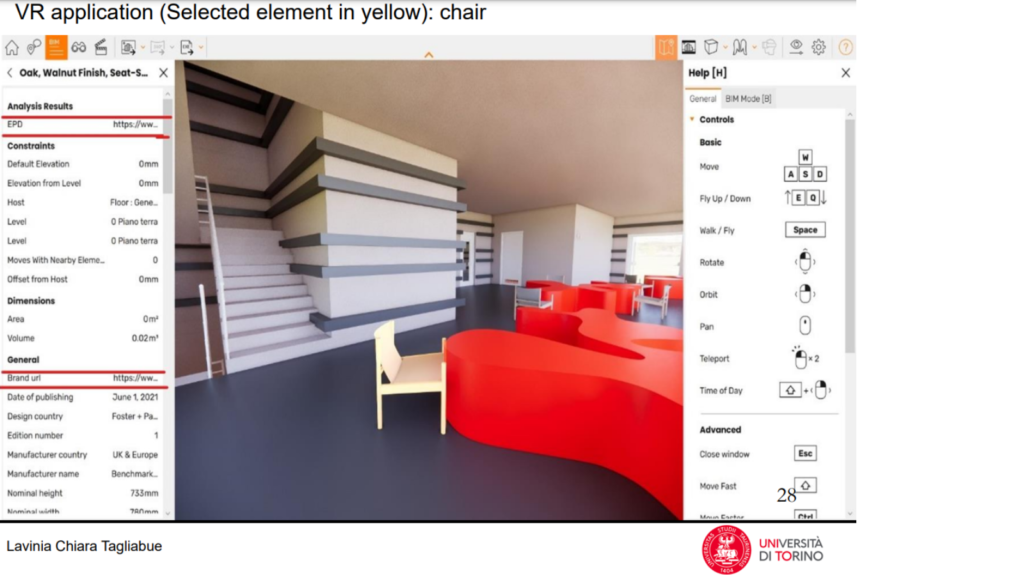

“When using digital twins for sustainability assessment, it is not just about collecting data but using it – analysing and implementing sustainable strategies based on that data,” highlighted Professor Tagliabue. A project at the University of Brescia campus used a digital twin of a lab building. It incorporated data from sensors tracking humidity, CO2 concentration, temperature, and other indicators, as well as feedback from students. The results were visualised using virtual and augmented reality.

The data-driven approach enabled researchers to make recommendations for improving indoor conditions for students, reducing the building’s environmental impact, and proposing more sustainable materials. It exemplifies how digital twins can be a powerful tool to improve indoor conditions and enhance sustainability in our buildings’ design and usage.

The journey towards sustainable homes needs a strong understanding of the building life cycle. As public and social housing providers, we can learn a lot from these projects that can be transferred to our own professional contexts. Life Cycle Thinking and digital twin technologies can help us to build a strategy towards resilient, eco-efficient buildings that respond to the evolving needs of our communities.

With thanks to Professor Alessandra Marini and Professor Lavinia Chiara Tagliabue who presented their work at our Sustainable Construction Topic Group meeting in Brescia. Eurhonet members can find detailed resources on Life Cycle Thinking and Digital Twin technologies here.